Episode Description

Two stories about how the humanities can provide healing for people during and after incarceration. The Mississippi Humanities Council’s prison book club program provides intellectual stimulation and community for men and women at 16 Mississippi prisons. And in New Jersey, a theatrical program called Ritual4Return gives returning citizens the opportunity to create and perform their own rite of passage to mark their return to families and communities after incarceration. Get the transcript.

Listen

Humanities = is available on all major podcast platforms. Listen on your browser by using the player above or find your preferred platform here.

Guests

Carla Falkner

Mississippi Humanities Council

Carla joined the MHC in 2021 as Project Coordinator for the Prison Education program. A former MHC board member, she recently retired from a 30-year career as a history instructor and academic division head at Northeast Mississippi Community College.

Will Underland

University of Mississippi

Will Underland has been a book club facilitator at Marshall County Correctional Facility for two years. He is also a PhD candidate in English literature at the University of Mississippi and holds a master’s degree from Middle Tennessee State University.

Kevin Bott

Ritual4Return

Dr. Kevin Bott is founder and executive director of Ritual4Return, Inc. He earned his master’s degree and his doctorate, both in Educational Theater, from the Steinhardt School at New York University. Kevin is the director of Rutgers Arts Online at Mason Gross School of the Arts.

Show Notes/Learn More: Mississippi Humanities Council’s Prison Book Clubs

Founded in 1972, the Mississippi Humanities Council (MHC) is a private nonprofit corporation funded by Congress through the National Endowment for the Humanities. MHC creates opportunities for Mississippians to learn about themselves and the larger world and enriches communities through civil conversations about our history and culture.

MHC’s Prison Education Program includes college courses and the book clubs featured in this episode. With support from the Mellon Foundation and in partnership with Mississippi community and senior colleges, MHC works with the Mississippi Community College Board (MCCB) and the Mississippi Institutions of Higher Learning (IHL) to support courses that fulfill basic degree requirements, prepare them for the workplace, and help students recognize and cultivate the humanity of themselves and others. MHC also provides funds for student academic support to help prison education programs meet the federal requirements to become Prison Education Programs where students can access Pell Grants.

Further Reading

Download the list of books read by Mississippi Humanities Council prison book clubs.

This feature on the book clubs in the Clarion Ledger: “MS prison book clubs adjust amid Trump-era cuts. How they work, affect inmates’ lives”

This moving piece in The Mississippi Independent from Alan Huffman, facilitator of the Inspired Readers club at the Wilkinson County Correctional Facility, reflecting on the clubs and their impact and sharing what club members drew from Station Eleven.

This follow up piece from Huffman, also in the Independent, about a special book club meeting in which combat veterans zoomed in to the prison book club to jointly discuss Ishmael Beah’s memoir of his experiences as a boy soldier during Sierra Leone’s infamous civil war.

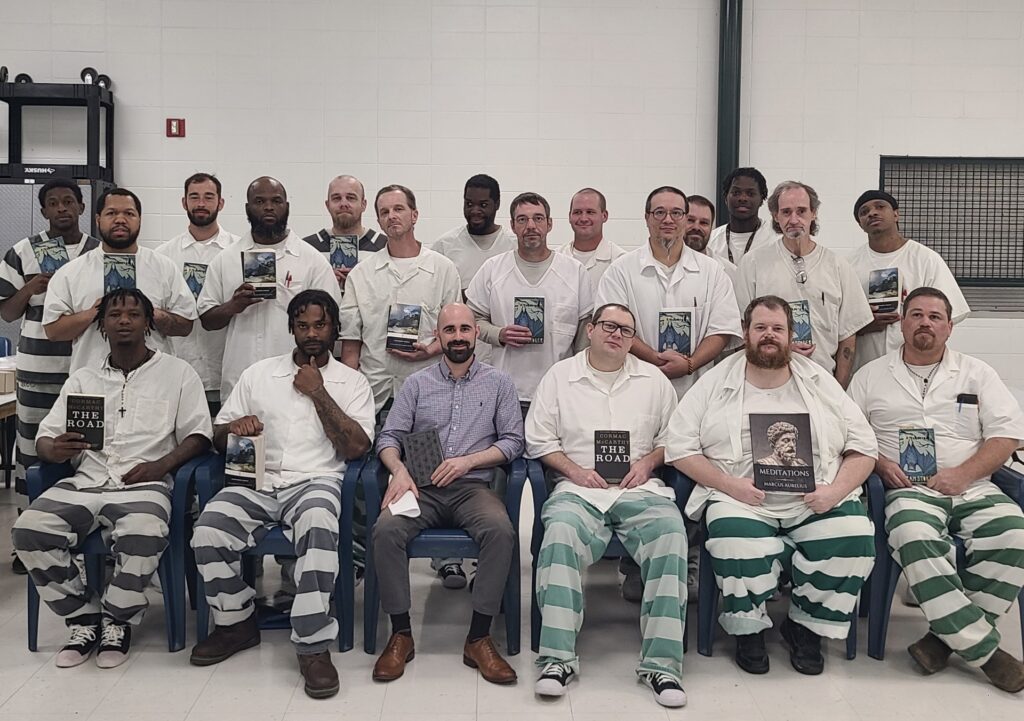

The Lit-Con Book Club at Carroll County Regional Correctional Facility. All the books they are holding (The Road, Count of Monte Cristo, Dracula, and Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations) were book club selections.

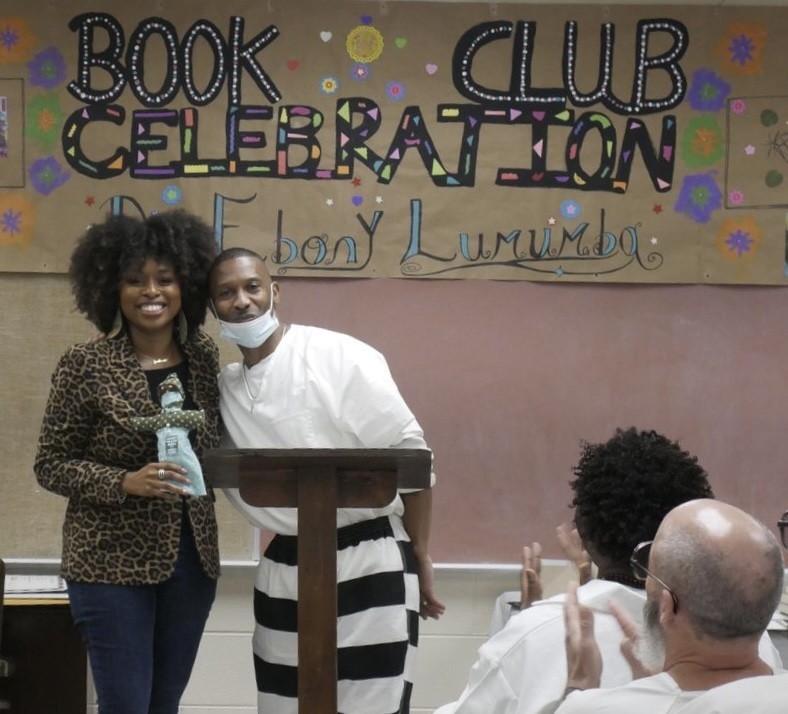

An event at the Freedom Within Book Club at Mississippi State Penitentiary/Parchman. This is the original MHC prison book club. One of the members is presenting their facilitator, Dr. Ebony Lumumba, with a Gullah doll that he made.

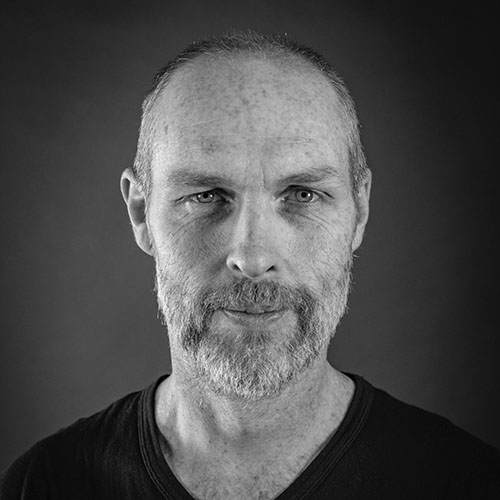

Author Joseph Earl Thomas signing copies of Sink: A Memoir for the Just Readers at Marshall County Correctional Facility (the book club Will facilitates). Thomas did book talks at two prisons as part of the 2024 MS Book Festival.

Show Notes/Learn More: Ritual4Return

Ritual4Return is a grantee of Humanities New York and the New Jersey Council for the Humanities.

Ritual4Return (R4R) is a 14-week program through which groups of returning citizens undertake a process of creating and performing a homecoming rites of passage. The process helps participants as they transition from incarceration to freedom. It is a demanding journey, pushing people intellectually, physically, emotionally, and spiritually as they define and then cross the thresholds that mark their individual and collective transition from bondage to freedom.

This program is for anyone who has ever been incarcerated for at least a year. It doesn’t matter how long you were in or how long you’ve been out. Ritual4Return is meant for people who feel traumatized by the impact of their incarceration, and/or who feel shame and feelings of stigma about their past. R4R is a healing and transformative tool for anyone who seeks to move on from their experiences of prison and into a new life.

Further Reading

This piece on NJ.com: ‘Can I tell my story?’ Previously incarcerated people find their voice on stage in new program”

This profile of Kevin Bott on Rutgers Today: “Rutgers Theater Project Supports Formerly Incarcerated People Reentering Society”

Program participants perform wearing handmade masks during the culmination of the 14-week experience.

Drumming and masks are used by participants to perform their rite of passage at the end of the program.

Family and friends of the participants attend their final performance. In this photo, a participant, having removed his mask, embraces someone who has come to support him.

What are Humanities Councils?

Our nation’s 56 state and jurisdictional humanities councils are nonpartisan 501(c)3 nonprofit organizations established in 1971 by Congress to make outstanding public humanities programming accessible to everyday Americans. Councils are funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) and connected by their national membership association, the Federation of State Humanities Councils.

Episode Transcript

Read Episode Transcript

[Theme music plays]

Kevin Bott: We have created a rite of passage which degrades millions, and then we don’t do anything to bring them back into the embrace of the community.

Carla Falkner: Prisons are dehumanizing places, and the book clubs—sitting in a group, having people listen to your ideas—that is humanizing.

Hannah Hethmon (Narration): You’re listening to Humanities =, a podcast about real individuals, organizations, and communities making a real difference through the humanities.

I’m your host Hannah Hethmon.

Humanities = is a production of the Federation of State Humanities Councils.

In this episode, you’ll hear about two humanities programs improving the lives of people currently and formerly incarcerated: in Mississippi, a prison book club program invites participants to explore their own humanity in the context of our larger culture, and in New Jersey, a theatrical program gives formerly incarcerated people the opportunity to create and perform their own rite of passage to mark their return to families and communities after incarceration.

We’ll start in Mississippi, where the Mississippi Humanities Council runs 16 book clubs for men and women in 12 different state prisons. To learn more about this program, I spoke to Carla Falkner, Project Coordinator for the humanities council’s Prison Education Program, and Will Underland, a PhD candidate in English literature at the University of Mississippi and book club facilitator at the Marshall County Correctional Facility.

Will Underland: It’s a once-a-week, hour and a half meeting of between 20 and 30 guys, who show up to the club having read a quarter of a book. We typically read a book a month. I prepare some open-ended questions about the text and invite the guys to discuss it. It gives the members a chance to think about and discuss ideas they might not otherwise have the chance to. And it’s sort of friendly, low stakes environment. There’s no grades or education credit, just thoughtful discussion about whatever the book happens to be about.

Carla Falkner: Each of our Mississippi Humanities Council book clubs is facilitated by a humanities scholar, and the members— in cooperation with the facilitator—get to choose their books. Our only requirement is that those books can lead to some meaningful humanities related discussions. But beyond them it’s up to them and their interests, and they end up with this wide range of books, going from classic fiction to recent best sellers, there’s memoirs, there’s other nonfiction, and we’ve had some short story anthologies, and even a couple of clubs dip into poetry.

Hannah: So, Carla, why was this program created. How did Mississippi Humanities identify the need and why did you think your team was a good group to address it?

Carla: In 2021, we got a Mellon grant to fund community colleges teaching in prison, and one of those programs was at Mississippi State Penitentiary, what’s commonly known as Parchment. And we were just a few months into the program when one of the prison educators asked me, she said, I’d like to start a book club. Do y’all ever sponsor anything like that? Is that the kind of thing you would do? Well, our tagline is that “the humanities are for everyone,” and with 19,000 Mississippians incarcerated, it certainly felt like this was everyone. This was part of reaching out to a new group.

Hannah: And beyond that initial idea, what was the need that you felt this was addressing? If there’s already college education, right, college courses, what’s the book club offering?

Carla: There’s multiple answers to that, but part of it is just what all of us gain from humanities programming. You know, we all are able to have a little bit richer lives and richer understanding of the world around us because of it. We have found these guys to be incredibly hungry for the interaction of the book clubs and for the intellectual stimulation, and I think, for the understanding of the world around them. And the book clubs have helped to provide that.

Hannah: The same reason that so many people are in book clubs everywhere in the country, around the world…

Carla: Right, exactly.

Hannah: So, Will, from your perspective, how does this program work? From agreeing to become a facilitator, what are all the steps? What is the process like? What goes on at meetings?

Will: In terms of, like, determining a book list and book selections. Basically, I pick a handful of books that seem that seem like they’re going to be interesting to talk about. The guys vote on what they want to read, and Carla gets them approved and ordered.

During the actual book club meetings, we talk about all kinds of things and do our best to stay on topic. But, you know, sometimes letting the conversation wander a little bit leads to some interesting ideas. And maybe, maybe the best conversations we’ve had are kind of the ones that get a little off topic.

Currently we’re reading The Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler, and we were talking about the genre of dystopian fiction and post-apocalyptic fiction, and we’d previously read The Road by Cormac McCarthy. And we were, sort of as a group, reflecting on why they were drawn to these post-apocalyptic stories and together, we kind of stumbled on the idea that there’s a strange and kind of uncanny overlap between the situation of incarcerated people and the situation of people living in a post-apocalypse. Like, think about the phrase “Judgment Day” as this, like a delineation of two separate halves of your life. And so, I think this, this, these dramas of living in a. In a post-Judgment Day or post-apocalyptic world, sort of strangely resonates with people who are incarcerated.

Hannah: I’d like to hear more stories about these people, about these individuals who are experiencing incarceration and the book clubs and the impact it’s had on them. You know, I’d like to hear from both you your favorite stories, of moments that really illustrate like what this does, what this means to them and how it impacts them.

Will: I’d say the first really memorable moment came pretty early on. We were reading the novel Sing, Unburied, Sing by Jesmyn Ward, part of which is set at Parchment, the prison that Carla mentioned earlier, and some of the guys had had actually served time at Parchment, and so were able to critique and kind of contextualize the books representation of parchment, and they had this sort of practical expertise that, you know, I don’t think, in my experience, is not often found in grad school or maybe academia in general. And I think spending time in prison, you really learn not to judge a book by its cover or by the labels that come with incarceration. A lot of the guys are genuinely insightful about the about the books we read. There’s a guy who’s a doctor, like an MD in a previous life. There’s a guy, Randall, who has a degree in theology. We’ve got at least one guy who’s a military veteran whose experience you know comes into play often in some of the books we read, and they bring this experience to bear on these conversations. And so, to me, it seems like the book club gives them an opportunity to offer something from their past as a positive contribution and not maybe just feel totally defined by their present situation, is sort of making part of their past real in a in a positive way, if that makes sense.

Other memorable moments…we’ve had several of the authors that we read visit in person or Zoom in and join the book club we had. We talked with the novelist and travel writer Paul Theroux twice. He zoomed in and, you know, regaled us with his many travel tales. Really nice, really interesting guy to talk to, Sister Helen Prejean, who wrote Dead Man Walking, Zoomed in and talked to the guys, and they got a lot out of that. And I think the fact that these well-known writers take time out of their day, you know, to spend an hour talking with the book club goes a long way, like regardless of what the conversation is about.

Hannah:

Will, how long have you been doing this particular club, and have most of the people been with you the whole time?

Will: It’s right at two years now. The book club fluctuates, but there’s, there’s a core of maybe 10, 12, guys who have been there basically the whole time, who kind of seem like they wouldn’t miss it for the world.

Carla: You know, in talking about things that really stand out, I don’t know that any story stands out any more than a member of the club at Parchment, which calls itself Freedom Within, who wrote us a note and told us that before joining the book club, he was suicidal. He had totally lost the will to live, and some of the other men picked up on just how down he was and how dangerous it was, and they invited him to the book club. They invited him to the book club, and then there was a creative writing program going on at that time. They invited him to it. He said, “Those things saved my life,” you know. And partly it was just being in there and getting some mental stimulation. I’ve had guys tell me that that you know, when you’re in prison, one of the dangers is just your brain just kind of shutting down. And this helps provide that, that stimulation we all need. But even more than that, I think, is that he found a camaraderie in the book club. You know, Will talks about his 10 to 12 core guys. Well, they’ve got a camaraderie, and that makes a difference for them. And so, I think that’s been one of the things that’s been so powerful in the book clubs growing. When we first start them, it is prison staff that does the recruitment program director, educator, a chaplain. But once it gets going, the members are recruiting for themselves.

Hannah: Can you talk more about this desire, this hunger for this kind of deep engagement with the text? People talk about, “Oh, people don’t read anymore.” And yet here, here are people who are eager to get into the written word. Can you talk more about that and why they connect with that, why that’s valuable to them.

Will: I mean, as a graduate student at the University of Mississippi, I teach freshmen and sophomores, and I think that that’s true—you know what you just said—that hunger is true for the guys in prison and for the college students I teach. I think it’s a culture-wide hunger for the arts and humanities. The same way some of the guys in the book club are being introduced to a certain type of intellectual stimulation. A lot of 19- and 20-year-olds are similarly being introduced to that kind of intellectual stimulation. And I think there’s a lot of reasons why that’s the case. Maybe they’re not the same reasons in in the two different populations, but whatever it is, I think the arts human humanities get treated as a sort of decoration on the economy, right? And if you can fit in time to read a book that allows you to escape from something or distract you, then you’re getting your humanities in. And I couldn’t disagree with that perspective more. I think, I think the humanities, they’re foundational. And if certain populations are being denied the opportunity to access the humanities, that’s a facet, I think, of the well-documented tendency to dehumanize, in this case, incarcerated people.

And I should stress, I think it’s about—and this book club is about—creating opportunity and access. You know, sitting in a room and talking about books, it’s not how everyone wants to spend their time, and that’s fine—in prison or out of prison. But as Carla’s story illustrates, you know, other people need this type of conversation, and I think literacy in general, or access to reading and writing, has always been political and inseparable from issues of race and class, as is the issue of mass incarceration in the US. So, I understand the work of prison book clubs as ultimately a kind of small but necessary form of resistance to that historical pattern of withholding and insulating the arts and humanities.

Hannah: And so, Carla, Will answered my question first, but maybe you—from your own perspective— of all the problems in the world that need our time and money. Why are these prison book clubs? Why are prison book clubs anywhere but in Mississippi, especially worth funding and putting time and effort for? And why should people care that there’s money for these projects,

Carla: The book clubs really do, I think, play a role in helping to prepare people for re-entry into society. You know, being in that group, learning to share ideas, sometimes discussing controversial issues, teaches some basic social skills. It teaches interaction with others. It builds confidence that you’ve got somebody like Will listening to what you have to say. It makes you realize that what you have to say is important and it matters. It helps build critical thinking. So you know, there’s a pragmatic perspective. There another way is that educational programming has been shown to actually reduce violence in prison to make prisons safer better places. And I believe the book clubs are a part of that. I mean, we’ve just heard about that, the camaraderie that can exist between these men, and so that’s another reason that that it, and I think it’s why the staff is so welcoming of this kind of programming.

But you know, in the end, prisons are dehumanizing places, and the book clubs—sitting in a group, having people listen to your ideas—that is humanizing. And you know, we do evaluations periodically, and the most repeated comment it’s just gratitude for having a place to freely express yourself, to be able to share ideas, to be respected, to be treated with some dignity. And so, I feel like that as much as anything you know, that book club gives them a place to explore their own humanity and the culture of the world around them.

Hannah: Well, what a place to end. Thank you both so much.

Hannah (Narration): For our second story, I spoke to Kevin Bott, a college administrator at Rutgers University and the founder and Executive Director of Ritual4Return. Ritual4Return is a 14-week theatrical program in which returning citizens, formerly incarcerated people, create and perform their own homecoming rite of passage to mark the transition from incarceration back into society. I became aware of Ritual4Return because of their connection to the New Jersey Council for the Humanities, which has awarded the initiative two grants to support the work.

But before we hear from Kevin, I want to share the voice of a program participant, a man named Eddie. This clip is from a video created by Ritual4Return, which you can find in full on their website. You’ll hear, Eddie reflecting on his experience in the program and as well as scenes from his final performance at the end of the 14-week journey.

[Clip plays from Ritual4Return video]

Hannah Hethmon: So, what’s the origin story for Ritual4Return? Where did this idea come from? How did you see a need, and how did you decide to step into that?

Kevin Bott: I was volunteering and eventually working for a New York based nonprofit called Rehabilitation Through the Arts. That’s actually the organization that people will know now as the inspiration for the movie Sing Sing. And so, I was creating theater and supervising other artists creating theater inside a number of New York State correctional facilities.

One of the actors who was incarcerated told me that he was getting out on parole. And he asked me if there was any theater back in New York City because it was so meaningful to him and it really changed his life. And that was in 2007. And I didn’t, had never thought about what happened when people got out because I was working inside, but it led me to the NYU library, where I was a graduate student at the time. And I started to read about this phenomenon called reentry.

And what I discovered in this body of literature was kind of a sub-literature about the potential for ritual and specifically rites of passage that could sort of counteract the rite of degradation, the ritual that happens on the front end when people move from citizen to felon or citizen to outcast or however you want to say that.

But there’s never anything on the back end to restore people into their place as a citizen within the society. And so that’s the need that I felt I was trying to address by beginning to think about what role ritual and rites of passage could have in people’s journey home.

Hannah Hethmon: Hmm. So, what, in this context, what is a rite of passage? And you said a little bit about that, but why is it important to have a rite of passage at this stage? How does that serve people? Why is that necessary versus perhaps just a group therapy session, for example?

Kevin: Yep. Yeah, it’s a great question. Well, rituals are things that we do on a regular basis with conscious intention that gives shape to our life. It brings meaning and purpose into our lives. And those things can be sacred, like going to a religious service once a week, or they can be secular, like getting together for a family dinner or celebrating the Super Bowl with friends.

A rite of passage is a very specialized kind of a ritual. And the purpose of a rite of passage is to facilitate major life transitions. And so we know them from things like puberty rights or matrimonial rights, where we know that we need something to mark these big changes that we go through. And in fact, without them, people can be adrift or never kind of take a step into the next stage of their lives. And those rites of passage are important, not only for the individuals that are going through them, but for the whole community. They’re kind of an affirmation of the values of the community. for example, a boy goes through a puberty rite to become a man, it is an affirmation of the values of that community. What does the community need from their men

And so in our contemporary moment we have created perversely a rite of passage which degrades millions of people by taking them from the role of citizen and putting them into a role that is less than citizen and then we don’t do anything to bring them back into the embrace of the community. And it’s a major life transition when you’ve done 10, 15, 30 or more years behind bars away from quote unquote normal life to then come back with really nothing more than a bus ticket and a plastic bag full of your belongings. And so what can we expect for the mental health and emotional health and well-being not only of those individuals, but of the families they return to, of the communities they return to, if we don’t offer some antidote to the degradation they’ve experienced.

Hannah: Hmm. So walk me through the journey a participant goes on in Ritual for Return. How do they get connected with the program? Or is there like an application process? And then what are the steps? What’s the scene by scene as they go through this journey?

Kevin: I’m not very picky about who comes into the program. To me, if you have been impacted by this system and you have spent time behind bars and you are coming home, simply the fact that you have sought me out and you have expressed interest in being part of this tells me that you’re ready enough to go through the project, to go through the experience.

Three hours a week, we meet in a donated space in Newark and the heart of the work, as I said, is storytelling and narrative. I mean, we are using a lot of the tools of theater and a lot of the work we do on a week-to-week basis is embodied. We’re drumming. We are moving our bodies. We are connecting the movement to the memory of experience. And then we are writing and talking stories. And one of the key pieces of reentry literature that I found so fascinating when I was studying was that one of the key dimensions of ending a life of crime, of kind of getting out of the game, as they say, is one’s ability to what they call re-biograph, which is to rewrite one’s story, to reframe one’s story in such a way that what had been seen as a shameful sequence of events, that really allowed one to stay in a place of shame and feelings of stigmatization. They could be reframed so that that same story could be seen through a lens of purpose and meaning. And the most common way that that people experience that is to say, “Okay, I went through that because there must be a greater purpose for me,” “My gang experiences must be because I’m gonna help young people not make the same mistakes that I made.”

And so that’s why we work on the narrative the way we do. And in the context of people who have also gone through similar experiences, people can say, wow, that’s not unique to me. A lot of people went through abuse, neglect, family addiction, and all the things that I went through as a child, so it makes sense that I landed where I did because all these men or women landed where they did and we have similar backgrounds. And so that’s what we’re doing week by week. And ultimately what we are getting to is a one-time only event, which is the rite of passage where they collectively and individually are going to perform their stories for an audience of family members, loved ones, the wider community, in the way that they want to express it.

It’s really their opportunity, for many of them for the first time in their lives, to stand up and say, “This is who I am.”

Hannah: So, they’re coming in with this idea of ritual, rite of passage. You’re doing theater workshop things: storytelling, moving the body, that whole kind of narrative and storytelling plus movement to start getting ideas flowing…

Kevin: Yes, yes, we’re drumming, we’re making masks. We’re talking about the role masks have played in their lives. So yeah, they’re doing all sorts of creative things, which, you know, for many, if not all of them, you know, it just lights up a part of them that they haven’t had access to before. You know,

Prison is designed to dehumanize. And in many ways, in the cruelest forms, it’s intended to break a person. It’s intended to humble a person to the point of full surrender and submission. And that means giving up access to a lot of pieces of one’s humanity. And theater and narrative and storytelling and movement, I mean, we’re doing all of the most human of things as a way to restore that sense of whole humanness. And so, you know, it’s activating and exciting and yeah, we’re doing all of those things every single week.

Hannah: That, I guess, starts to come together and starts to look like something as they start to decide what their ritual is in that place of discovery, culminating in that performance in front of their friends and family and loved ones where they sort of bring this all together in a kind of a moment of stepping over.

Kevin: Yeah, and you have to know, mean, even after everything I explained to you, a lot of people do come in still thinking like, well, are we putting on a play? This is a play, right? I’ve had people tell me they couldn’t quite wrap their head around even what we were doing until they had done it on the day of the ritual. It’s very hard to conceptualize until you go through the fire of the experience and then it all clicks into place and is an amazing experience for them, but yeah, it’s really asking people to take a giant leap of faith into something that is completely unknown to them. I mean, most of them have never stepped foot in a theater, seen a play. This is all for them. Suddenly they’re in something on stage, live, with lights on them in a darkened room. I mean, it’s a very terrifying and exhilarating experience.

Hannah: So can you share a few favorite or most meaningful moments, examples, stories from the work that have showed the impact, really bring home how this affects people and where it takes them?

Kevin: There’s a moment in which the rite of passage culminates and it is, as I said, it’s kind of like vows similar to wedding vows where the person still wearing the mask that they’ve created, which they wear through the course of the rite of passage. They speak the commitments that they’re making to themselves, perhaps to their family, maybe even to the community about who they are and who they commit to being. They’re surrounded by their family. We invite anyone who’s there to support this individual to come up and they come and surround this person. And, you know, as they’re speaking, the family’s crying, they’re crying, I’m crying, the audience is crying, everyone’s crying. You know, they have notes that they’ve written, but they’re speaking from the heart. And finally, they reintroduce themselves there for the first time, the audience hears their name, they have not spoken their name throughout the event. And so, they say, I’m, you know, proud to reintroduce myself to my family and my community, my name is and they say their name and they take off the mask. So, we see their faces for the first time, and hear their name for the first time.

And its cathartic, it’s incredibly moving. And I hear from the families just what the impact is on them, what it is on sometimes the participants’ children, sometimes adult children are there in the room. And what it means to hear their father’s story or their mother’s story…I’m getting emotional as I speak about it.

Coming back from prison is like coming back from a war zone. It’s like a veteran coming back from war. You don’t know how to speak about these experiences. And for many people, the people who receiving the person coming home kind of don’t want to deal with the experience because they went through their own hardship. And the instinct is to put it behind you and try to move on with life after however long. And the problem is you can’t just move on because everyone’s traumatized and yet no one knows how to have the conversation, even initiate the conversation.

And what the ritual does, what I’m told it does for the families is it breaks this giant ice wall that has been living between people in their own homes, sometimes for a decade or more. And it starts a conversation that’s needed to happen for a long time. So that’s very healing. I’ve heard women say to the room full of other returning citizens at the group meeting, other than the birth of my children, this was the most important event of my life. This allowed me to step into myself in a way that I never had before.

I see it in the way people keep showing up to support the nextcohort of initiates through the ritual. So, you know, what had been just, you know, six, eight, ten people going through the process before loved ones now on either side of the ritual space, you know, we have 20 graduates with their own djembe drums drumming in support, being part of the ritual. mean, it feels like you’rein a real ritual. It’s a real thing. You know, it’s not a play. And so just testimonial after testimonial speaks to the healing dimension, the rehumanization aspect of the work.

Hannah: On a more practical note, this podcast is secretly about promoting Humanities Councils. Not so secret because I just said it, but can you say a bit about how funding from humanities councils has supported Ritual4Return, you know, across the years and why small grants are helpful for organizations like yours?

Kevin: Yeah. Well, first of all, I say this all the time: without the humanities councils that have supported me, I don’t know that we ever would have launched. It was Humanities New York that first offered me funding. And that was a matching grant that I was able to match with support from the Columbia University Justice Lab. And that then brought the interest of an acting studio in New York City that had a justice focused to it. so, you know, that very first $5,000 matching grant from Humanities New York was the seed that allowed this to begin to flourish. That, I mean, the funding itself, of course, was important because I was, you know, looking just to go broke personally by continuing to try to fund this out of my own pocket. But the legitimacy that the Humanities Council support gave to the project was crucial. I continue to maintain that relationship with Humanities New York, even though I moved to New Jersey years ago.

And then when I came to New Jersey, once again, my first funder, the first source of support was New Jersey Council for the Humanities. And again, they have jumped into this project with their whole hearts. They reach out to ask me how it’s going, what they can do to support, know, can they make an introduction here or there? It’s just, it’s become more, like I said, the funding is always important. We need small funding, big funding, all funding. But with the humanities councils, I mean, I feel like they embody the values of the humanities, which is connection, human support, relationship, engagement, ongoing dialogue about what is this work about.

Hannah: Finally, Ritual for Return has begun its first ever program to train affiliates in these methods to kind of expand this work. So how do these trainings, this expansion of the program to other facilitators factor into the future? And what are your hopes for this training and for the future of Ritual for Return more broadly? What’s next?

Kevin: I’d always wanted to expand this program. I took a small team of graduates out to Chicago in 2024 for a convening of several state councils that were supporting justice work.

Hannah (Narration): Side note: This convening of humanities councils was organized by Illinois Humanities.

Kevin: And we did a little demo project of Ritual for Return. And from there, we had about eight teams from different states coming to us saying, how can we bring this back to where we are? And then the federal administration changed and everyone’s funding went kerflooey and priorities changed.

So right now we have two teams from Minnesota and from Massachusetts who are walking with me on really an experiment. It’s a pilot initiative that we’re figuring out together. The idea is that this year they are going to travel to New Jersey, the Minnesota team, I think with some council support, to come witness one of our rituals in person. So, there’ll be about teams of three or four that all come to witness this.

It is incredibly exciting to me because, you know, to think that in a year, a year and a half, there will not just be one Ritual4Return, but there will be three Ritual4Returns across the country. And I hope that will then, you know, lead to more attention and notice for other communities to say, how do we bring it here? And the vision of Ritual4Return is that this should be available to everyone who has gone through the degrading rite of passage into incarceration so that for the benefit of not only individuals, not only families, but for the benefit of the entire society, we can bring whole, healthy, healed people back into our communities.

Hannah: Yeah, it’s a beautiful idea when you’re talking about people coming back, participants coming back and supporting the idea that not just that’s happening in one city, but as it’s spreading out to other cities, more and more people coming back to support other people’s healing journey. And you have this kind of ripple effect of people out in the world who think about healing, who think about supporting other people, who think about their experience as a tool for connecting and for, you know, making the world a better place. And what an incredible transformation that could be even as it grows on a small scale. So, I’m really excited to follow along in the future. Once I interview someone, I always feel connected. So really excited to follow in the future to see where this goes. And I really appreciate you sharing the story with me.

Kevin: Thanks so much. Yeah, you well, as you can tell, I love to talk about it. I’m as curious as you are.

Hannah (Narration): Thanks for listening to Humanities =, a podcast from the Federation of State Humanities Councils. You can learn more about the humanities councils and programs in this podcast, see episode transcripts, and explore additional content on our website, statehumanities.org, that’s statehumanities.org.

Our nation’s 56 state and jurisdictional humanities councils are nonpartisan nonprofit organizations established in 1971 by Congress to make outstanding public humanities programming accessible to everyday Americans.

If you’d like to learn more about your humanities council or support their work through a donation, you can do so at statehumanities.org/directory or by searching your state name + “humanities council.”