Stories of CHamorro Women with Northern Marianas Humanities Council

by Sydney Boyd, Humanities in American Life project manager

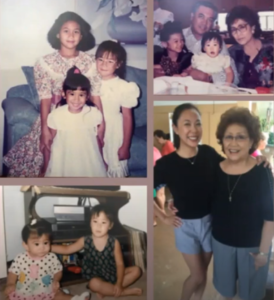

When Kayle Tydingco asked her grandmother if she could interview her as part of a research project for her thesis about CHamorro women and culture, her grandmother said “Sure, but my life isn’t interesting—no one’s going to read it.”

Tydingco is CHamorro Japanese, and although she was raised in a CHamorro household, she often felt disconnected from the culture. This feeling inspired a thesis project involving first-person interviews, historical texts, and archival work that culminated in a series of short stories. Tydingco delved into her process of discovery in a conversation titled “Tiningo’ Famalåo’an: Oral Histories and Non-fiction Stories of CHamorro Women” on October 23, 2020, as part of Northern Marianas Humanities Council’s Humanities Fridays series.

Tydingco said she realized she didn’t know who her grandmother was independent of her familial connection, and she set out to uncover the stories of so-called “ordinary” women. Through the lens of intersectionality, a concept conceived by Kimberlé Crenshaw that understands social constructs like race and gender overlap in systems of discrimination, Tydingco narrowed her scope to women who were of CHamorro descent born between 1940 and 1945 and focused on family, education, and occupation. She settled on CHamorro values, US colonization, and Catholicism as three essential points of intersectionality that determined agency and influenced the choices these women made.

“I use the term Tiningo’ Famalåo’an to refer to the knowledge shared by the CHamorro women interviewees,” Tydingco said. “This cultural repository, Tiningo’ Famalåo’an, stems from cultural values, gender roles, and behaviors.”

Through her interviews, Tydingco identified three main themes that ran through each woman’s story: courtship chaperones, economic need, and upward mobility. Courtship chaperones, people who accompanied unmarried couples on dates, were often younger siblings, Tydingco learned, and at the time these women were starting families, the idea of “women’s work” was expanding from being a housewife to entering the workforce while still acting as primary caretakers at home.

One of her interviewees talked about how full-time work was important to buy a home, furniture, a car, and afford tuition for Catholic school, among so many other things to support the family.

“There’s bills everywhere, so there was no question. Everybody in the family worked, my sister worked, so the only thing is that my mom didn’t work because after she got married and she started having children—it was the old days you become a housewife, but not in our time anymore. The time has changed,” Tydingco quoted.

Tydingco took these interviews and transformed them into a short story collection titled CHamorro Women in the Driver’s Seat: Steering & Storytelling. Each chapter corresponds with one of the through-running themes that Tydingco discovered. The first chapter, “Håfa na klasen palao’ian hao?” which translates as “What kind of woman are you?” explores what type of wife a woman is supposed to be; the second, “Tighten your Belt,” is about finding a balance between economic and personal growth; the last chapter, “Che’cho Låhi and Che’cho Famålao’an: Rosita’s CHamorro Fairytale” tells a story about love and gender performance in CHamorro contexts.

After reading an excerpt from her last chapter, Tydingco ended with a call to action.

“I encourage everyone to record stories,” Tydingco said. “COVID has taught us that we never know how much time we’re going to have, what better way to spend your time than record stories of people in your life?”

This post is part of “Humanities in American Life,” an initiative to increase awareness of the importance and use of the humanities in everyday American life.

This post is part of “Humanities in American Life,” an initiative to increase awareness of the importance and use of the humanities in everyday American life.

Photo Credit: Kayle Tydingco and Northern Marianas Humanities Council