This post is part of “Humanities in American Life,” an initiative to increase awareness of the importance and use of the humanities in everyday American life.

“Caring Labor Sustains Life”: Women’s Labor Activism in the Appalachian South

by Sydney Boyd, Humanities in American Life project manager

Think of the word “labor” in American history, and the image that o ften comes to mind is of working men employed in industries like coal mining or steel work.

ften comes to mind is of working men employed in industries like coal mining or steel work.

“These are men who worked for wages, and we associate them with the building of modern America. The coal miner in particular is an icon of the American working class. But what about domestic workers, farm laborers, or workers in the service industry? What about non-wage work?” said Dr. Jessica Wilkerson in a virtual West Virginia Humanities Council “Little Lecture” on May 30.

Her lecture, “Women’s Labor Activism in 20th Century West Virginia and Appalachia,” draws from Wilkerson’s 2019 book To Live Here, You Have to Fight: How Women Led Appalachian Movements for Social Justice, which looks at working-class women’s activism in the Appalachian south to understand the rapid transformations of the gender system in twentieth-century United States and how those transitions intersect with labor, class, race, politics, and family.

“Appalachian communities have provided an important realm to understand the history of women’s involvement in grassroots politics and social movements for several reasons,” Wilkerson said. “They witnessed swift changes in the labor system with the development of single industry economies, thus allowing me to understand how women navigated waged and non-waged labor under evolving twentieth-century capitalism.”

A key term in Wilkerson’s research is “social reproduction,” or care work, which has historically fallen to women.

“Caring labor sustains life. And it also sustains the capitalist system,” Wilkerson said. “What would it mean to center social reproduction when we discuss the meaning and value of labor?”

The concept of social reproduction stems from feminist theory (Wilkerson specifically draws from Evelyn Nakano Glenn, whose work focuses on Black women’s domestic work), but the term hasn’t yet been seriously applied to Appalachian history. In the Q&A period after her lecture, Wilkerson explained why social reproduction has been missing from that conversation.

on Black women’s domestic work), but the term hasn’t yet been seriously applied to Appalachian history. In the Q&A period after her lecture, Wilkerson explained why social reproduction has been missing from that conversation.

“Appalachia is coded as very masculine, with very masculine workers who are really iconic in American labor history, and that of course is really important—I’m not saying that we shouldn’t focus on that history and that we shouldn’t tell it with a lot of nuance, but it’s tended to erase this other aspect of the labor history, especially in the coal fields.” Wilkerson said. “There’s also been a tendency to identify women in the coal industry by their relationships to men.”

This history begins in the centuries leading up to the 1900s, Wilkerson noted, when white working people settled on land that had belonged to Indigenous societies. They ran small farms, while wealthier whites used slave labor. As the railroads expanded in the late 1800s, the coal mining industry boomed, and a gender shift happened in the division of labor: women maintained not only the home but now also tended the family farm while men headed to the mines.

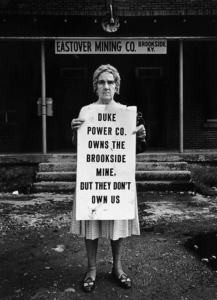

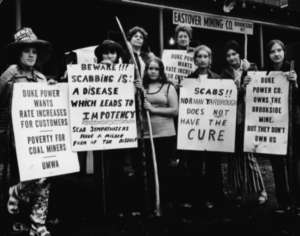

Women’s involvement in labor rights meant more than supporting their husbands, brothers, and sons working in the mines—women had their own motivations tied to their own labor, Wilkerson said.

“They saw the world through the eyes of people who tended to children, broken bodies, hungry workers, and distressed neighbors,” Wilkerson said.

For example, in the 1960s and 70s Sudie Crusenberry was taking care of two men in her family: her father, who was smothering from black lung disease, and her husband, who had been severely injured in a mine accident. She nursed her father through an extremely difficult death, and she cared for her husband daily while still maintaining the house and raising her four kids. She later became a leader in the 1973 Harlan County, Kentucky mine strike.

“She often explained her care work as an important driver of her activism,” Wilkerson said. “She believed that unionized workers had better conditions in the workplace, which also meant that women might have to take care of fewer injured people, or that when they did, they had more resources at their disposal.”

And Wilkerson said we’re still seeing the effects from women’s labor activism, particularly during the pandemic. She noted that in the late twentieth century there was a simultaneous decline in industry and rise of paid care work made up mostly of women workers, although they were still paid a much lower wage than men who were industrial workers.

And Wilkerson said we’re still seeing the effects from women’s labor activism, particularly during the pandemic. She noted that in the late twentieth century there was a simultaneous decline in industry and rise of paid care work made up mostly of women workers, although they were still paid a much lower wage than men who were industrial workers.

“This is the case even as we define them as essential workers in the era of COVID,” Wilkerson said. “We should listen to those essential workers about their needs in the present, taking a cue from women labor activists in Appalachia’s past, and I would encourage us all to build working-class solidarity that meets the needs of working families.”

Photo Credit: West Virginia Humanities, Dr. Jessica Wilkerson; www.earldotter.com